I am currently in Vienna for a conference (not related to anything medieval) and also able to visit some interesting places in this beautiful city. One of these places is the Schatzkammer in the Neue Burg. In this museum are some early medieval garments on display, as well as some religious relics (such as a piece of the holy cross and the holy lance). As a modern woodworker, the holy cross fragment did not impress me; but in my re-enactment incarnation, of course, was awed by these fine relics.

![]() Furthermore, there were several items on display that were related to the order of the golden fleece (instated by Charles the Bold). Two of them were liturgical vestments (antependium) of the order of the golden fleece dating from between 1425-1440. The vestments are made of linen, embroidered with precious metal and silk threads and adorned with pearls and glass pastes. They show images of the apostles, saints, prophets and other biblical persons, but also some pieces of furniture of the late fourteenth - early fifteenth century. Interestingly, you can see a transition of older types of seating furniture to newer versions. Not all names of the biblical figures were discernible on the vestments, and not all figures could be photographed due to the lighting on the display of the vestments.

Furthermore, there were several items on display that were related to the order of the golden fleece (instated by Charles the Bold). Two of them were liturgical vestments (antependium) of the order of the golden fleece dating from between 1425-1440. The vestments are made of linen, embroidered with precious metal and silk threads and adorned with pearls and glass pastes. They show images of the apostles, saints, prophets and other biblical persons, but also some pieces of furniture of the late fourteenth - early fifteenth century. Interestingly, you can see a transition of older types of seating furniture to newer versions. Not all names of the biblical figures were discernible on the vestments, and not all figures could be photographed due to the lighting on the display of the vestments.

Furthermore, there were several items on display that were related to the order of the golden fleece (instated by Charles the Bold). Two of them were liturgical vestments (antependium) of the order of the golden fleece dating from between 1425-1440. The vestments are made of linen, embroidered with precious metal and silk threads and adorned with pearls and glass pastes. They show images of the apostles, saints, prophets and other biblical persons, but also some pieces of furniture of the late fourteenth - early fifteenth century. Interestingly, you can see a transition of older types of seating furniture to newer versions. Not all names of the biblical figures were discernible on the vestments, and not all figures could be photographed due to the lighting on the display of the vestments.

Furthermore, there were several items on display that were related to the order of the golden fleece (instated by Charles the Bold). Two of them were liturgical vestments (antependium) of the order of the golden fleece dating from between 1425-1440. The vestments are made of linen, embroidered with precious metal and silk threads and adorned with pearls and glass pastes. They show images of the apostles, saints, prophets and other biblical persons, but also some pieces of furniture of the late fourteenth - early fifteenth century. Interestingly, you can see a transition of older types of seating furniture to newer versions. Not all names of the biblical figures were discernible on the vestments, and not all figures could be photographed due to the lighting on the display of the vestments.On the right is a writing desk with open shelves. The apostle Bartholomew sits in a chair with a high back, with likely a chest under the seating. This is a 15th and 16th century type chair. Some kind of bookshelves.

A saint (Jacobus?) sitting on a chair with a high back.

The apostle Matthew sits on a rounded back chair. This type of chair first appears in the 15th century.

Also here a lectern is shown.

Prophet Daniel is sitting in a chair with a high rounded back.

On the right a simple chest with a lock is seen, on the left a movable lectern.

King David sits on a throne like chair. Next to him is a lidded chest with a lock.

This saint is sitting on a small bench with a lectern next to him.

These benches were common during the 15th and 16th century, but also known in the 14th century.

The prophet Ezekiel is sitting in a chair with a high backrest.

On the right is a bench and on the left a writing desk.

Job is sitting in a chair with a rounded back.

The other furniture shown here is a small chest on the right and a lectern with a movable piece.

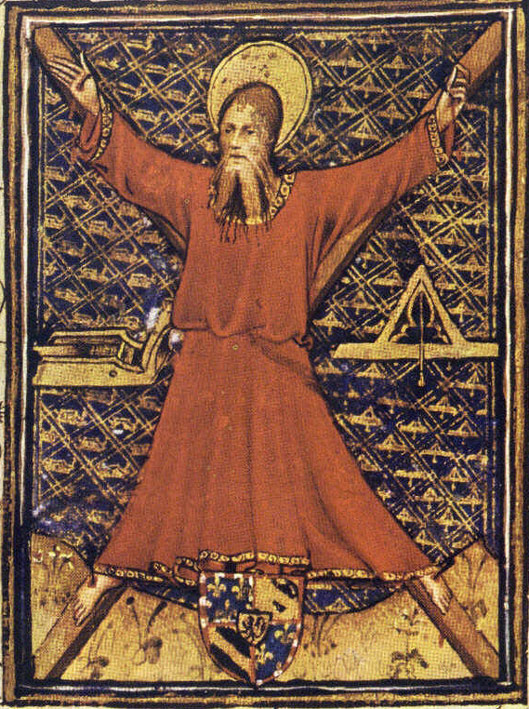

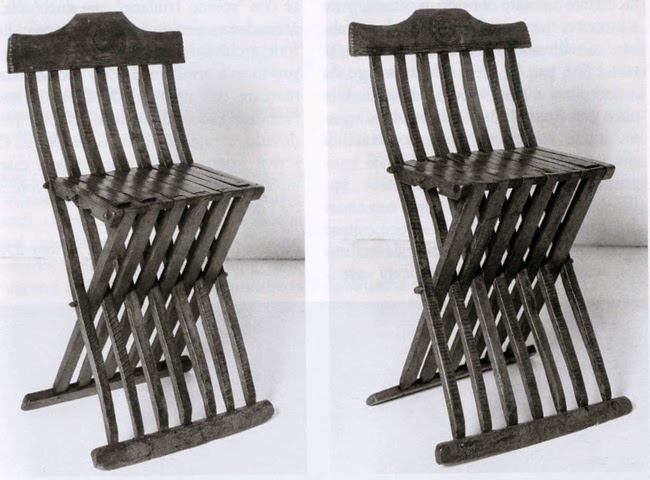

The prophet Joel is sitting on an X chair with a high back.

This type first appeared at the end of the 14th century and remained in use into the 15th century.

The prophet Zacharias sits on a chair with a high backrest.

A lectern for writing is shown on the left.

The apostle Judas Thaddaeus is sitting in an x-chair with a turned armrest.

This type of chair is typical for the second half of the 14th century. It is old-fashioned at the time of the vestment.

Apostle Matthias sits on a high-backed square chair is a chair found in the second half of the 15th century.

A very modern chair for the vestment. Also a lectern and bookshelves are shown.

This poor saint does not have any furniture.

Apostle Andreas. He sits on a chair, but it is hidden by the clothes of the saint.

The apostle Philippus sits in a square chair with a high backrest.

Apostle Simon sits in another chair with a rounded back.

An armoire to store books stands next to him.

Last, apostle Thomas sits in a square chair with a high backrest. It looks as if the backrest is turned, making it an old-fashioned chair. A small armoire with bookshelves is next to him.